Dr. Matthew Links refuses to see barriers between disciplines. The research that Links does as an Assistant Professor at the University of Saskatchewan’s (USask) College of Agriculture and Bioresources is hard to categorize.

To say Links’ work is on the cutting edge would be accurate, but it doesn’t tell the full story. His research is at a nexus point — a space where computer science and biology meet to fulfill goals that neither field can accomplish on its own.

Such is the nature of the field of bioinformatics. Links uses his highly specialized expertise to answer challenging questions in agricultural sciences.

“I don’t believe that the problems are solvable by either (computer science or biology) in isolation,” said Links. “To solve the questions we want to answer, we necessarily need both.”

Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary science, using computer technology to analyze data drawn from life sciences that would otherwise be too complex to manage. Many elements of genomics, such as DNA sequences, contain so many individual pieces of data that it would be nearly impossible to work with them without the help of computers.

“You’ve got data sets that are so big, you need both a computational understanding and … some kind of life science to understand all of the problem. You can look at that as one side supporting the primary idea in the other, or that both of them have primary ideas and things to gain from each other.”

Where science and technology meet

Links parents’ paths most certainly influenced his own. His father was versed in computers, mathematics and commerce, and his mother taught anatomy and other medical technology fields.

“Sitting around a kitchen table, it was never weird for me that you might talk about computer science at the same time you talk about something like human health,” said Links.

But when he was choosing his own academic pursuits, Links ended up going with both. Even as a student, Links was able to see the possibilities coming at the intersection of health sciences and computer technology.

“This was around the time the human genome was getting sequenced, so there was a realization that these disciplines around computer science and life science were colliding. And that really interested me.”

Links ended up studying both computer science and biochemistry simultaneously at USask, something he said wasn’t commonly done at the time. After that, he pursued a Master of Science in Biological Sciences from the University of Windsor, and a doctorate in veterinary microbiology at USask.

For Links, interdisciplinary training is not only helpful for exploring genomics — it’s a necessity.

“If you look at the number of characters that make up those genomes — we’re talking about things that are, in some cases, hundreds of millions of characters, and in others, billions of characters — that’s easily for me getting into the ‘wait a minute, that isn’t tractable by a human.’”

“It is tractable by a human working with a computer. So, it seemed like a space where there was going to be new types of opportunity … these interdisciplinary fields are going to be the ones that come together for this kind of thing.”

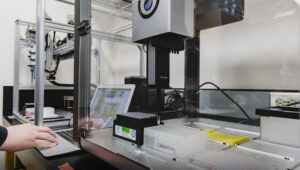

Inside Dr. Links’ Lab: Charlie (an OpenTrons OT-2 liquid handling device) and Rosita (an OpenTrons OT-1 liquid handling device) are running simple example protocols (moving water and food coloring to create art in a microtitre plate). (Photo: Carey Shaw)

Bringing “Star Trek devices” to the farm

Links’ current areas of research seem just as diverse as his education. One of his projects involves microbiome studies in connection with swine, which is currently being funded by the national research body Swine Innovation Porc.

The microbiome is a term for the collection of microscopic organisms living on or in the bodies of living things. The swine project examines the “gut microbiome” of pigs through the use of fecal swabs and next generation sequencing.

The goal of the swine project is to find a correlation between strong, healthy swine and the presence — or lack thereof — of certain organisms in swine microbiomes. That correlation could lead to improvements in the health of herds for animal producers.

DNA sequencing has been accelerating at a phenomenal pace in recent years and Links’ group is focused on turning these data into actionable knowledge. Of the newest generation of sequencing technologies is the use of nanopores — a protein through which a strand of DNA could pass and be analyzed — to enable portable sequencing, which Links’ team has been using in studies of chicken and cattle.

“The reality of this ‘Star Trek tricorder’ is, this is real,” said Links. “It may be too expensive to sequence every animal, but the impact this will make to a producer, to have this in their hands, literally, is revolutionary.”

Links sees a future where producers are using this technology as being not far off.

“The technology and science has leaped so far that we can be excessive in what we generate, and then triage the information to make the very simple, applied decision we need to make.”

The cast of characters in a cross-disciplinary classroom

Scattered across a desk in Links’ office are various LEGO figurines, each with their own colourful accessories.

They were each assembled by one of Links’ team members as an introductory exercise. It highlights an important part of his bioinformatics field: the number of diversely talented people who are working together to break boundaries in science.

“I forget that this is work. It’s more like I’m running around with the Big Bang Theory cast of characters and we’re talking about all these things, and we don’t know any better to stop or to not try to do this thing where everyone else says ‘that doesn’t make sense.’” said Links. “We say, ‘Why?’”

Links is also helping others reach that nexus as an assistant professor for the university, teaching the next generation and providing the same kinds of opportunities that made the difference early in his academic career.

Already, Links said he’s seeing students cross disciplines before they’ve finished their studies.

“We’ve taken some of the animal science undergrad students and had them do some of this DNA sequencing. And that’s crazy, because at least three of them now are about to go into their final year of veterinary medicine. “They’re going to come out as trained veterinarians who don’t see a limit as to why they couldn’t do DNA sequencing in their practice.”

It’s a far cry from the dual-degree path Links had to make for himself when he was beginning his own academic career. And it’s continuing to grow as science continues to push the boundaries of what humans and technology are capable of.

“We do some things that, on the surface, make no sense to anyone else. But it’s legitimately part of not seeing that barrier between things.”

Thank you to the College of Agriculture and Bioresources (USask) for submitting the article and photos.

Photo: Dr. Matthew Links.

Credit: Carey Shaw