It is assumed by governments in many developed countries that consumers support the replacement of petroleum-based products with biomass-based products, which leads to continued investment of public funds into the development and production of bioproducts and continued political support for bioproduct industries. But is this assumption correct? Considerable research has been done on consumer acceptance of biotechnology in Canada and in numerous other countries but there is a lack of similar research exploring consumer acceptance of industrial bioproducts.

It is assumed by governments in many developed countries that consumers support the replacement of petroleum-based products with biomass-based products, which leads to continued investment of public funds into the development and production of bioproducts and continued political support for bioproduct industries. But is this assumption correct? Considerable research has been done on consumer acceptance of biotechnology in Canada and in numerous other countries but there is a lack of similar research exploring consumer acceptance of industrial bioproducts.

Not only is it important to know the current level of support for bioproducts among consumers, it is also important to know what influences consumer support. As suggested by existing literature, perceived risks and benefits are often investigated as the primary drivers behind consumer acceptance or support of new technologies (Peters et al. 2015; Nevitt et al. 2006; Costa-Font and Mossialos 2007; Frewer et al. 1998; Fischer and Frewer 2009). Most consumers have insufficient knowledge of new technologies, yet are forced to make purchasing decisions. These decisions are largely based on a trade-off between perceived risks and benefits (Costa-Font and Mossialos 2007). The federal government, through Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), as well as private companies involved in the bioproducts sector have the ability to shape consumer perceptions of risks and benefits associated with bioproducts and therefore can influence levels of consumer support.

The research discussed below focuses on estimating marginal effects that show the direct impact of increasing perceived benefits or decreasing perceived risks on the probability that a consumer will select “strongly support” when asked about their attitude toward bioproducts. This study was conducted using data from the 2011 Innovative Agricultural Technologies Public Opinion survey.

This research addresses two main questions. First, does the distribution of consumer support for bioproducts and biofuels differ when food versus non-food crops are used as biomass inputs? Second, what are the psychographic and socio-economic factors that influence consumer support for bioproducts and biofuels and do these factors differ if the consumer is evaluating support for bioproducts and biofuels made from food crops versus those made from non-food crops?

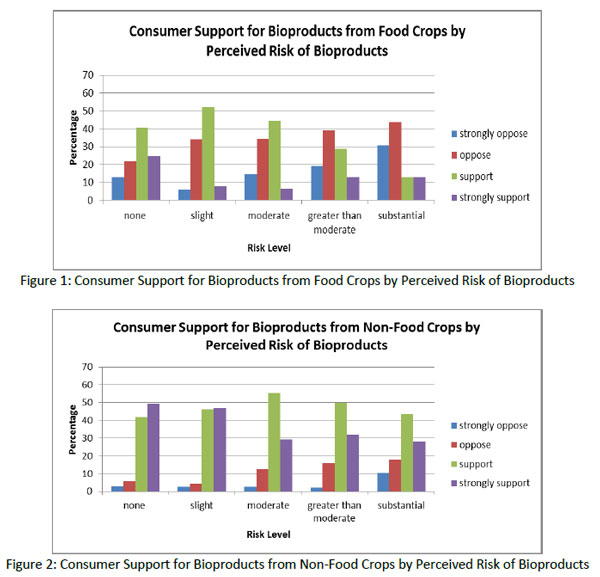

To answer the first research question, consumer support for bioproducts from food and non-food crops was cross-tabulated with consumers’ perceived levels of benefits and risks associated with bioproducts. The results showed that consumer support does depend on whether the consumer is evaluating bioproducts from food or non-food crops, as is evident in figures 1 and 2 below. For example, among those consumers who perceived substantial risks associated with bioproducts approximately 45% opposed bioproducts from food crops (in figure 1). However, when it came to evaluating bioproducts from non-food crops among those same consumers who perceived substantial risks from bioproducts, approximately 45% supported bioproducts from non-food crops (in figure 2).

To answer the second research question the marginal effects of numerous psychographic and socio-economic variables were calculated. The following trends emerged:

• Perceived risks are significant in determining consumer support for bioproducts and biofuels from food crops, but not significant when non-food crops are used;

• Perceived benefits are significant in determining consumer support for bioproducts from non-food crops and biofuels from food and non-food crops, but are not significant when evaluating consumer support for bioproducts from food crops;

• Perceived environmental impacts and confidence in regulations were only significant in determining consumer support for bioproducts from food crops;

• Familiarity with bioproducts was never significant; and

• Perceived future impact of biofuels significantly affected consumer support for bioproducts and biofuels from food crops only.

The majority of significant marginal effects had magnitudes of less than 10%, however, there were a few strong, statistically significant marginal effects. For example, those consumers who perceived moderate, great, or substantial benefits from bioproducts were 17%, 29% and 39%, respectively, more likely to strongly support bioproducts from non-food crops. Consumers who perceived little, moderate, great, or substantial benefits from bioproducts were also 22%, 17%, 33%, and 51%, respectively, more likely to strongly support biofuels from non-food crops. Consumers who perceived a negative future impact from biofuels were 11% more likely to strongly oppose bioproducts from food crops and 20% more likely to strongly oppose biofuels from food crops.

Interesting trends also emerged from marginal effects analysis of the socio-economic variables. Women were less likely to strongly support bioproducts and biofuels from non-food crops but more likely to strongly support biofuels from food crops. University graduates were less likely to strongly support bioproducts and biofuels from food crops but more likely to strongly support bioproducts and biofuels from non-food crops. Unemployed and retired consumers were less likely to strongly support bioproducts and biofuels from food crops. Lastly, consumers in New Brunswick, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan were less likely to strongly oppose bioproducts and biofuels made from food crops.

Returning to the two research questions introduced earlier, I can conclude that the distribution of consumer support does differ depending on whether food or non-food crops are used in the bioproduct or biofuel production process and consumers do consider different factors when determining their support for bioproducts and biofuels made from food crops and those made from non-food crops.

Another notable finding of this study is the significant gains in consumer support to be made by increasing perceived benefits. This is demonstrated by the large, positive marginal effects of consumers’ perceived levels of benefits on the probability that the consumer will strongly support bioproducts. Therefore, by assuming a promotional role to inform consumers of the benefits provided by bioproducts, AAFC and private bioproduct companies may be able to substantially increase consumer support for bioproducts and biofuels in Canada.

Kaitlin Kelly is an MSc. Candidate in the Department of Bioresource Policy, Business & Economics at the University of Saskatchewan Top photo: camelina – Linnaeus Biosciences / graphs submittedReferences Cited

Costa-Font, Joan and Elias Mossialos. 2007. Are Perceptions of ‘Risks’ and ‘Benefits’ of Genetically Modified Food (In)dependent? Food Quality and Preference 18: 173-182.

Fischer, Arnout R.H. and Lynn J. Frewer. 2009. Consumer Familiarity with Foods and the Perception of Risks and Benefits. Food Quality and Preference 20: 576-585.

Frewer, Lynn J., Chaya Howard, and Richard Shepherd. 1998. Understanding Public Attitudes to Technology. Journal of Risk Research 1(3): 221-235.

Nevitt, Johnathan, Bradford F. Mills, Dixie W. Reaves, and George W. Norton. 2006. Public Perceptions of Tobacco Biopharming. AgBioForum 9(2): 104-110.

Peters, Dorte Marie, Kristina Wirth, Britta Bohr, Francesca Ferranti, Elena Gorriz-Mifsud, Leena Karkkainen, Janez Krc, Mikko Kurttila, Vasja Leban, Berit H. Lindstad, Spela Pezdevsek Malovrh, Till Pistorius, Regina Rhodius, Birger Solberg, and Lidija Zadnik Stirn. 2015. Energy Wood from Forests- Stakeholder Perceptions in Five European Countries. Energy, Sustainability and Society 5(17): 1-12.