Bonus: Scroll down for a video with Scott Napper, Senior Scientist at VIDO, and USask medical historians Simonne Horwitz and Erika Dyck.

Saskatchewan scientists are not alone in their struggle to beat back Covid-19. Researchers from all disciplines are united in the effort to not only control the pandemic, but to also understand our response to the disease.

Scott Napper, Professor in the department of biochemistry, microbiology and immunology at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) and Senior Scientist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO) in Saskatoon, SK, is no stranger to infectious disease research, but he is taking on a new endeavour during the Covid-19 pandemic — co-teaching his first history course.

Napper will be delivering an interdisciplinary course on the history of infectious disease and vaccines alongside experienced medical historians Professor Simonne Horwitz and Professor Erika Dyck, who holds a Canada Research Chair in the history of health and social justice. The class is offered to undergraduate students at USask.

“We desperately need these interdisciplinary approaches in order to understand the causes and outcomes, but to also communicate them and make our communication resonate across broad and diverse audiences,” Dyck says.

As we approach one year of living within the restraints of Covid-19, many of us have looked to past pandemics as a way to help navigate the unique experience of living through one of the most disruptive global pandemics we have faced in a hundred years. But when it comes to pandemics, there appears to be no “one-size fits-all” definition. Instead, these events have wide variations in their impact, reach, and duration.

“What we saw with Covid-19 — the moment it was defined as a pandemic — was largely a judgement call,” Napper says. “It’s not like there is a specific number of people we are looking for and alarms go off and we say, ‘it’s now a pandemic.’ It’s more defined in general terms.”

Because of this, judging the severity of pandemics or predicting their impact may be difficult as it plays out in real time. But the cyclical nature of disease outbreaks allows us to respond to current or future threats by analyzing how we responded to similar threats in the past.

Napper sees Covid-19 as a bit of a warning shot. As much as Covid-19 has affected us, he recognizes that this pandemic could have been infinitely worse.

“I hope this serves as a bit of a wake-up call. We are always setting the stage for these things to happen, for example: population density, movement, and destruction of the environment. This will happen again,” Napper warns.

Horwitz has done extensive work on the AIDS crisis and Ebola outbreaks in Africa. She sees that pandemics, epidemics, and isolated outbreaks tend to accentuate pre-existing cracks in societal foundations.

“Epidemics always bring out the fissures in society and often it’s the same fault lines,” Horwitz says, “It’s around race, it’s around gender, it’s around class and we see that in almost every epidemic or pandemic we have faced.”

Horwitz points out that a number of different issues which seem unrelated to Covid-19 — like the Black Lives Matter movement or the rise of Trumpism — are fed by the heightened stress of the pandemic. Recognising the way this stress plays out within our society is fundamentally important.

Horwitz says that we, as a society, have become so individualized – and so has the discourse around Covid-19. For the anti-mask and anti-lockdown protests, the message has centred around the idea that public health can’t or shouldn’t tell the public what to do. Yet the mandate of public health is to tell people what is good for society. As Horwitz puts it, we see our individual rights as paramount to group rights, which should not be the case.

Dyck points out that identities have become intertwined with the Covid-19 response.

“Other things have become merged with different Covid-19 narratives and different identities that involve the idea of ‘Us vs Them.’ Pandemics intensify the divisions that already exist and the mapping of political and Covid fears have given way to a gulf of ignorance,” Dyck explains.

As a historian, Dyck is also interested in how Covid-19 will be perceived in the future, especially among today’s children.

“I am fascinated with what mark this pandemic will leave on the way that we interact with each other. What will the kids remember from this period? What marks of compassion and caution will they carry with them for the rest of their lives? For some of the kids this is what they know, this is their normal and for most of us, I think, we still think of it as an aberration of normal,” Dyck says.

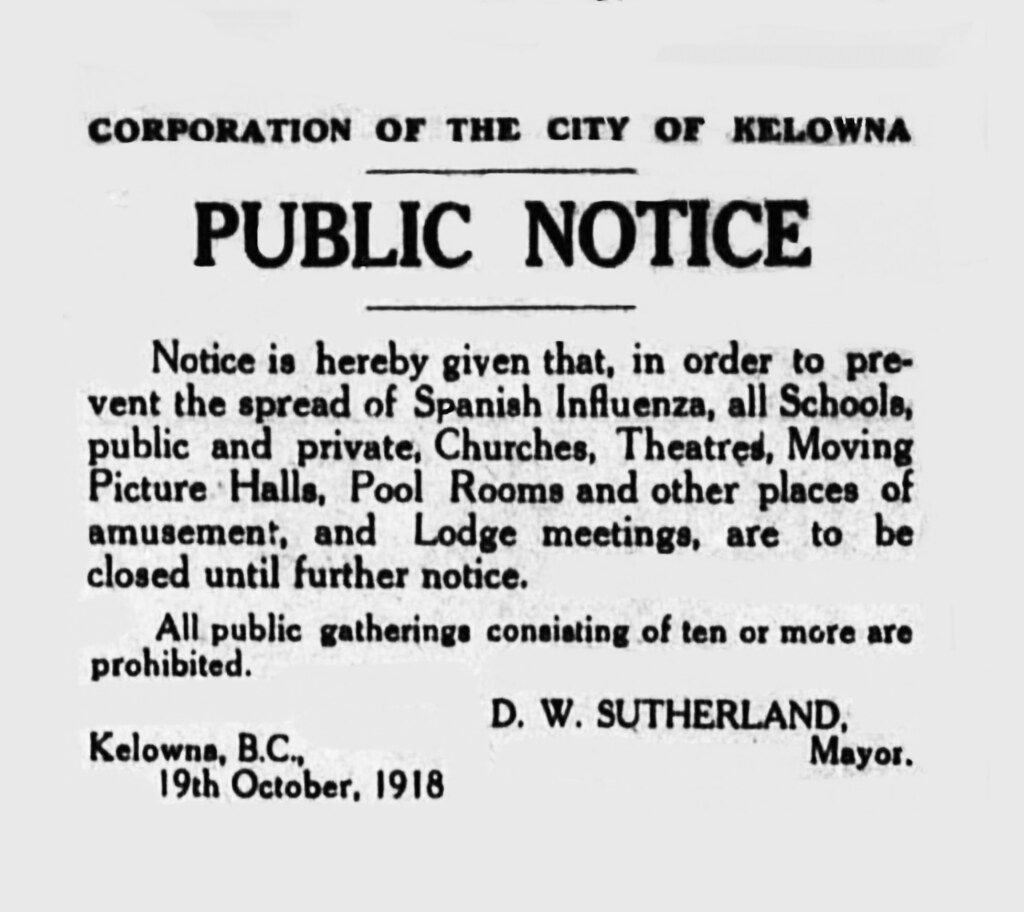

Images: 1) “St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps on duty during influenza epidemic (1918). Original from Library of Congress. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel. Original from Library of Congress. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.” by Library of Congress is marked under CC0 1.0. 2) “To Prevent the Spread of Spanish Influenza …” by JFGryphon is marked under CC0 1.0.